Electrification of off-highway vehicles isn’t new. What’s new is the combination of battery economics, tighter urban rules and a rapidly evolving global supply chain—forces that are pushing OEMs to rethink machine architecture, service strategy and the realities of charging on a jobsite.

Danfoss Editron’s Eric Azeroual on off-highway electrification trends

Electrification is often framed as the next big disruption for construction, mining and agricultural equipment. But in the off-highway field, “electric” has been hiding in plain sight for decades. Look at ports and mines and you will find machines that already exploit electric torque, efficiency and controllability, even if a diesel engine is still part of the system. In warehouses, electric forklifts and aerial work platforms have long been mainstream.

So why does electrification feel like a fresh wave now?

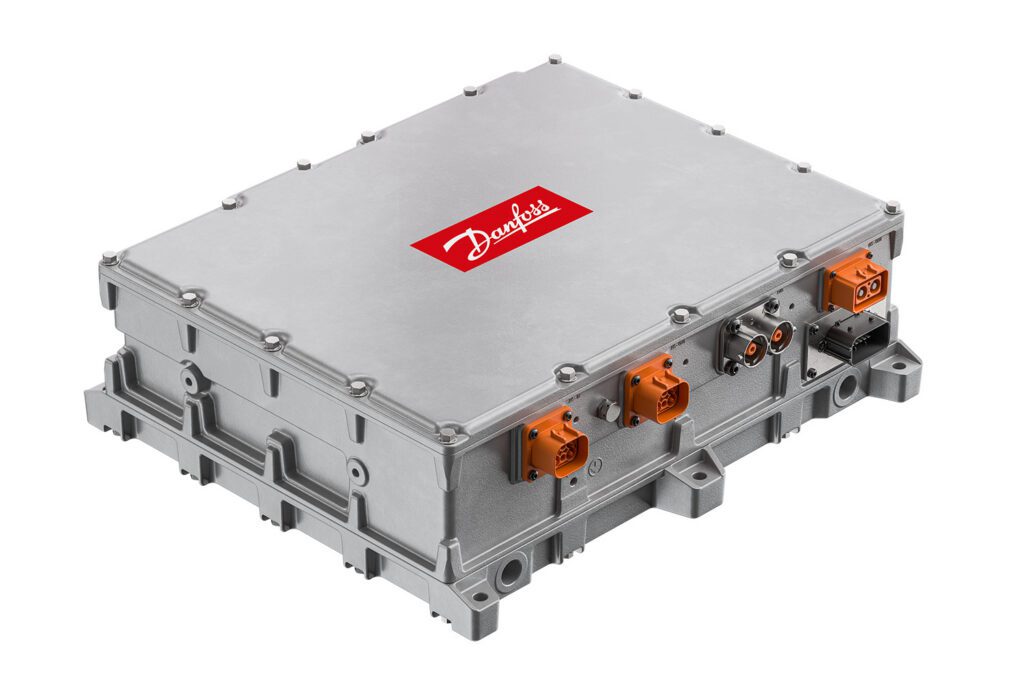

Charged recently chatted with Eric Azeroual, Vice President at Danfoss Editron (the electrification arm of Danfoss Power Solutions). He pointed to two accelerants: rapidly improving battery economics and the rising pressure of city-focused emissions standards. As he described it, off-highway is “going through a very big transformation,” moving away from internal combustion engines and conventional hydraulics toward electric and electrified hydraulics.

The real inflection point: batteries got cheaper and cities got louder

Azeroual argues that off-highway didn’t suddenly “discover” electrification. Engineers and end users have long understood the benefits of electric machines: power density, high torque at low speed, and the efficiency advantages that come from precise control.

The first thing that has changed over the last few years is the affordability of the energy storage needed to untether machines from the grid. Azeroual explains that the momentum of passenger-car electrification pushed battery cost down from roughly $1,000 or $1,500 per kWh” to $100 or $150, making it feasible to electrify a much larger slice of off-highway equipment—especially the “middle market” between tiny low-power vehicles and large, grid-connected machines.

The second accelerant is regulation, especially in cities. Emissions standards for machines operating in urban areas are tightening, and OEMs are weighing whether to keep investing in increasingly complex after-treatment systems or to redirect that investment into electric platforms and electrified work functions.

This combination is particularly consequential because construction dominates demand. Azeroual pegs wheel loaders and excavators as roughly 50% of the off-highway market, and he sees them as “poised to electrify quicker” for a very practical reason: their duty cycles often align with electrification better than outsiders assume. Many of these machines do not travel long distances, and they operate in defined spaces, with intermittent work and idle time. And because many operate inside cities, regulation and noise become immediate drivers. He offered a vivid example: an excavator operating in the middle of Paris may need to be electric to meet emissions requirements in the near future.

A two-speed voltage world: 48 V at one end, high voltage everywhere else

One of the clearest signs that off-highway electrification is maturing is that the debate is shifting from whether to electrify to how to electrify. For Azeroual, voltage is becoming the defining design fork.

The first wave is already here: compact wheel loaders and mini excavators built around low-voltage (typically 48 V) architectures. They are “low risk,” relatively straightforward to charge, and avoid the safety and integration complexity that comes with high voltage.

But he does not expect a smooth ladder that includes a significant medium-voltage category. Instead, he predicts a fast jump: either sub-60 V systems (the 48 V class) or high-voltage systems for most platforms beyond that—“two poles,” as he described it.

Two engineering drivers sit behind that jump:

- Charging rate and uptime. Higher voltage enables higher power transfer, which reduces charge time and protects equipment uptime, an essential economic variable in off-highway.

- Power and efficiency. When power requirements push beyond about 150-200 kW, higher voltage becomes a practical way to reduce current and resistive losses, improving system efficiency and lowering thermal burden.

Danfoss Editron is developing low-voltage and high-voltage solutions because those are the two segments in which OEMs are placing bets.

Azeroual also sees an important “bridge” between automotive and off-highway: heavy-duty trucks and commercial vehicles. In his view, advancements there are helping close the gap between passenger-car high-voltage ecosystems and off-highway requirements. Danfoss is selectively involved in on-highway electrification, he said, primarily when the technology can be carried back into off-highway products.

Why modularity is not optional in off-highway

In passenger cars, product strategy is built around standardization: a small set of interfaces, high-volume platforms and minimal variation. In off-highway, that assumption fails quickly. OEMs face wide variation in machine layout, packaging space, work functions and customer expectations, and volumes are often low enough that a “one-size-fits-all” approach can become a deal breaker.

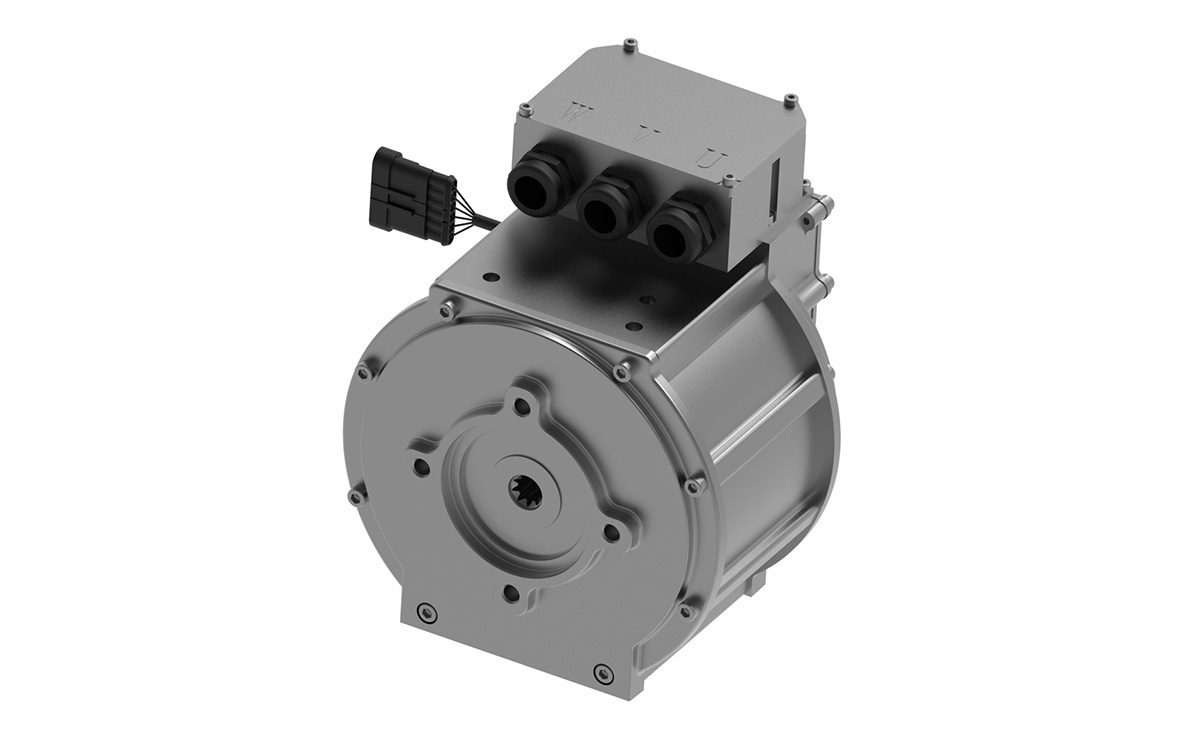

Azeroual offers drivetrain topology as an example. An off-highway machine can easily require five motors and five different inverters, and each of those components must mount, route and cool in a way that fits a specific machine layout. Unlike automotive, in which the interface might be standardized around a small set of packaging conventions, off-highway often demands different form factors—“pancake” versus cylindrical—and different mounting realities.

Modularity is not purely mechanical. Off-highway machines are increasingly sensor-rich—OEMs are demanding more inputs and outputs, more diagnostics and more freedom to calibrate software to match unique work cycles. Azeroual describes modularity as the ability to modify interfaces—shaft, spline, connectors—as well as the software itself, so that end users can calibrate behavior to a particular application.

This is where Danfoss leans on its controls background. Azeroual highlighted Danfoss’s long history with the PLUS+1 software architecture—about 20 years—as a framework that allows customers to “pick and choose building blocks” for their vehicle architecture.

The trade-off, he acknowledged, is cost. Adding options and configurability can increase part cost. But in off-highway, flexibility is frequently the price of entry, especially when customers order ten units rather than ten thousand. Azeroual suggested that suppliers built around high-volume standardization often struggle here, and that a lack of flexibility can even be perceived as “arrogant” in what is, despite the equipment size, “a small world” of industrial machinery.

He offered a concrete benchmark for how far this variation can go: a single motor family may exist in “350 different variants,” driven by mechanical interfaces, connector options and related configuration needs.

The business physics: ROI sensitivity and market cycles

Off-highway is an engineering market, but it is also a market governed by simple economics. Azeroual says that end users are “very sensitive to ROI,” and notes the historically incremental pace of machine innovation: if the machine does the job, buyers prioritize reliability and hours-of-operation improvements over radical redesigns.

Electrification is different because it forces a step change across the machine: architecture, components, controls and service. That creates opportunity, but also hesitation when business conditions tighten. He described the market as a “light switch.” When money is tight, innovation slows—when demand rises, appetite returns.

Azeroual also called out a cultural difference that can surprise engineers coming from automotive: in off-highway, prototypes can end up being sold. He contrasted this with passenger cars and commercial vehicles, where prototypes are built for validation and never reach customers. In off-highway, a prototype electric machine may be purchased quickly, because machines are often custom-built and buyers are eager for workable solutions.

That dynamic can create whiplash. Some OEMs built electrified machines and struggled to sell them immediately, leading to a “we did it for nothing” sentiment, which Azeroual described as short-sighted. He contrasted those reactions with OEMs that treat electrification as part of a longer strategy—leveraging learnings from other mobility markets such as marine and on-highway trucks.

China’s gravitational pull on the electrification supply chain

Azeroual did not sugarcoat the role of China in electrification. He conceded that China dominates the electrification supply chain—batteries, motors, inverters—and suggested that global OEMs and suppliers must consider what that means for cost and iteration speed.

China’s strategic focus at the Bauma China trade show in 2024, which was heavily centered on electrification. Chinese OEMs were not simply showing concepts—hey had machines available for purchase and deployment.

From an engineering standpoint, the more uncomfortable point is cost and iteration. Azeroual suggested that Chinese suppliers are further along in development cycles—he describes China as being in the midst of a “seventh evolution” of motor and inverter development, compared with “generation three” elsewhere.

Azeroual’s interpretation is that Chinese manufacturers have iterated aggressively enough to understand the “bare minimum” required to serve real applications, rather than over-designing for edge cases.

A hidden differentiator: distribution, service and local engineering leverage

In off-highway, buying a component is inseparable from buying uptime. Machines operate in harsh environments, under schedule pressure, and downtime can erase any cost savings quickly.

Azeroual framed Danfoss’s large distribution network as a strategic advantage that complements modular design. Distributors are not only sales channels—they can also act as local integrators and solution builders. He described seeing a distributor share an integrated solution built from Danfoss components—motor, pump and controls—and offer it directly to customers.

He also warned about the limits of low-price entrants who lack service infrastructure. A component may be inexpensive, but when the part breaks, the question becomes who can service it and how quickly the machine can return to work—off-highway’s definition of real value.

Right-sizing as cost strategy: what marine and continuous-duty markets teach

Azeroual offered an engineer’s answer to the cost problem: learn from harsh duty cycles where the physics are unforgiving.

He explained how Danfoss’s experience in marine and oil-and-gas applications—markets in which motors can run continuously near their limits—provides data that informs product design for off-highway. In traction, peak power may be brief. In marine, “the peak power is the continuous power,” and the system runs “continuously at the edge.”

That stress testing can reveal that many products are over-designed for off-highway applications.

For engineers, this is a critical theme: electrification is not just about making an electric machine work. It is about making it work at the right cost, with the right lifespan assumptions, and with materials and performance aligned to actual duty cycles.

The bridge technology: electrifying hydraulics before electrifying everything

Azeroual repeatedly returned to a pragmatic adoption path. Off-highway is conservative. If something is “too new,” it can stall. He suggested that this conservatism is part of why fully electric machines have not yet taken off broadly.

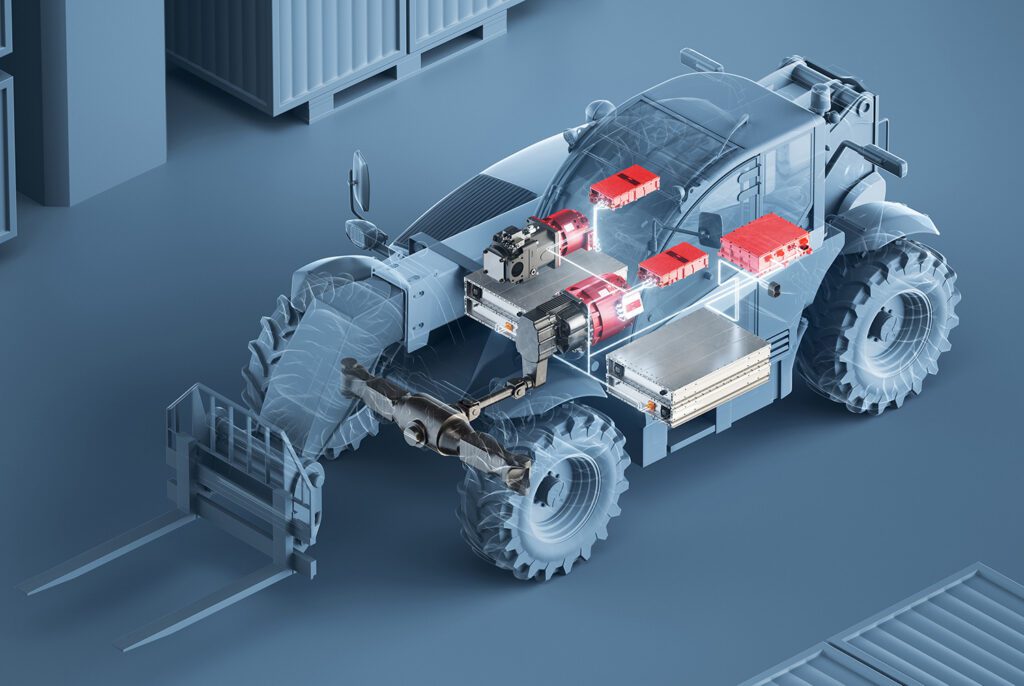

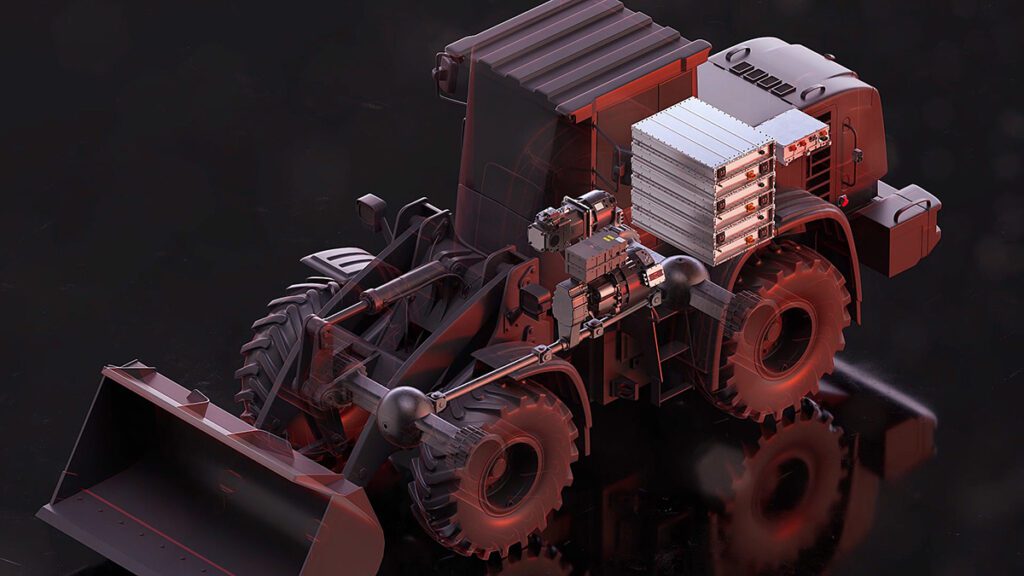

Danfoss’s near-term emphasis is electrifying hydraulics and improving hydraulic efficiency—essentially using electric control to reduce wasted energy and to make work functions more responsive. The underlying idea is to stop wasting energy “turning a pump,” and to control pressure and flow so that the system operates as efficiently as possible.

He also suggested that electrification enables new component design choices, such as high-speed pumps better matched to electric motors—on the order of 8,000 to 10,000 RPM—along with the potential for lower noise once the combustion engine is removed from the loop.

Azeroual highlighted one Danfoss example as a “best of the best” combination: pairing a digital displacement pump (DDP) with an electric motor. Digital displacement can modulate pump output to match demand, and electric motors allow speed to be adjusted dynamically, expanding the operating envelope and improving efficiency. He called the combination “a game-changer.”

Then came a forecast that will spark debate: Danfoss anticipates pure battery-electric machines to remain “less than 5% by 2030,” while electrified, efficient hydraulics could rise into the 20-30% range.

Whether or not those exact percentages prove correct, the directional message is clear: for many machine classes, electrifying the work functions may deliver ROI sooner than full battery-electric conversion—and that can be a bridge to deeper electrification later.

Seeing is believing: demos, application centers and operator acceptance

Technical arguments alone rarely shift off-highway buying behavior. Operators, fleet owners and rental companies need proof of performance under real conditions.

Azeroual described Danfoss’s Application Development Centers (ADCs) as a way to generate that proof. Danfoss takes in customer vehicles (or selects platforms with high innovation potential), implements new architectures and then invites customers to test them. He cited ADCs in Ames, Iowa; Haiyan, China; and Nordborg, Denmark; where Danfoss can rapidly prototype and demonstrate solutions.

Demonstrations matter because they reveal benefits that spec sheets rarely capture. One example is jobsite communication: electrified machines can be quiet enough for a spotter to talk to an operator while the machine is digging, potentially improving precision and teamwork. Azeroual agreed that these “other things that we didn’t expect” can shift perceptions quickly.But he also emphasized the counterweight: electrified machines are still more expensive. Adoption depends on solving charging and uptime in a way that fits the ways in which equipment is actually deployed.

Charging is a bottleneck—and it won’t look like highway fast charging

Charging is where off-highway diverges most sharply from passenger cars. Even as on-highway electrification is building an extensive DC fast charging network, off-highway equipment often cannot use it. “You’re not going to bring an excavator on the side of the highway” to charge, Azeroual said.

Instead, the question is what power exists on a jobsite—and how a machine can use it without slowing the work.

Azeroual pointed to a practical Danfoss product development: an onboard AC charging solution, the ED3 (Editron three-in-one). His framing is pragmatic: most construction sites already have access to AC power, while DC power is “very rare” on-site and only possible through new large power banks. By enabling meaningful AC charging—he cited 44 kW as an example—machines can recharge overnight or during breaks without requiring a dedicated DC infrastructure build-out.

He also suggested that equipment-rental economics could become a key enabler. Because machines are often rented, a rental company could match battery size and charging strategy to the job: the same platform with a larger battery for a remote site, or a smaller-battery version when overnight charging is available. That kind of modularity, he argued, could help “break the barriers of entry.”

What this means for engineers designing the next generation of machines

Azeroual’s perspective makes one thing clear: off-highway electrification is not a single technology trend. It is a systems transition shaped by economics, policy and a rapidly evolving global ecosystem.

For engineers, several practical implications stand out:

- Architecture decisions are converging. Expect a split between low-voltage compact machines and high-voltage mainstream platforms, driven by charging power, efficiency and the 150-200 kW-plus reality of many work cycles.

- Modularity is an engineering requirement. Mechanical interfaces, packaging, I/O and software calibration flexibility are not “nice to have” in off-highway; they are central to winning programs across diverse machines and low-to-medium volumes.

- E-hydraulics is likely to be a major near-term lever. Electrifying and optimizing hydraulic work functions can deliver efficiency, noise and controllability gains without requiring every machine to become fully battery-electric overnight.

- Charging must match the jobsite. Onboard AC charging, right-sized batteries and fleet/rental planning may matter more than replicating the passenger-car DC fast charging playbook.

Off-highway will not electrify evenly. Some segments—compact urban machines and duty cycles with predictable charging—will move quickly. Others—long-duration field work, remote jobsites and exceptionally harsh duty cycles—will take longer. But the direction is increasingly clear: electrification, in one form or another, is becoming a standard design constraint, not a side project.

from Charged EVs https://ift.tt/j82fKgZ

No comments:

Post a Comment